Dear Activists: When Does Love Become Imperialism in Disguise?

A Sharp Look at the Ego-Driven Crusades Masquerading as Compassion

Love That Destroys

"I love China. I just want its government overthrown, its political system dismantled, and its entire social fabric rebuilt in my image. But it’s out of love—I promise."

You hear this kind of thing more often than you’d think, especially from Western activists, tech-savvy expats, and professional human rights warriors. They’ll tell you how much they admire Chinese people, how beautiful the culture is, how much they enjoyed the dumplings in Chengdu—before launching into a diatribe about the need to “free” China from its own government.

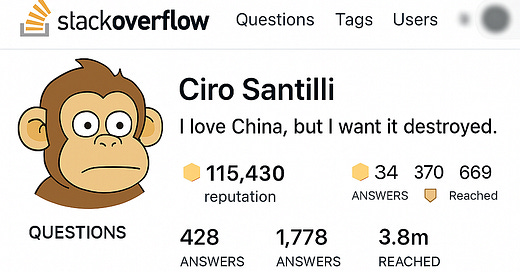

Some even go so far as to build entire public personas around this contradiction. Take Ciro Santilli, a software engineer who brands himself online as a “China lover” while actively campaigning for the downfall of the Chinese Communist Party. He claims he doesn’t hate the Chinese people—just their government, their legal system, and the institutions that shape daily life. Small stuff.

But here's the thing: when your “love” for someone involves plunging them into chaos to suit your ideological vision, it’s not love. It’s something else. It’s control. It’s ego. And sometimes, it’s imperialism—just with better marketing.

So let’s ask the uncomfortable question that never gets asked:

When does “love” become imperialism in disguise?

Western Obsession: Why China Triggers the Moral Crusade

Western media rarely runs out of things to criticize about China. From the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang to internet censorship, to the situation in Tibet or the handling of COVID, the coverage is relentless, emotionally charged, and rarely nuanced.

That doesn’t mean there are no real issues in China. But it’s telling how the outrage seems to be selectively deployed. Take Saudi Arabia—an absolute monarchy with no elections, routine executions, and brutal crackdowns on dissent. Does it get the same daily coverage? Not even close.

Why does China get under the West’s skin so much more?

Part of it is ideological. China’s success as a one-party, state-led system challenges the Western belief that democracy and liberalism are prerequisites for prosperity. It's uncomfortable—maybe even threatening—for people raised to believe that freedom of speech and multiparty elections are the only path to a good society.

Part of it is fear. As China grows economically and technologically, some Westerners don’t just see a trade rival—they see a civilizational competitor. That fear makes it easier to paint China not just as different, but as dangerous.

And part of it is good old-fashioned moral superiority. The West loves a crusade. John Oliver did a full segment mocking China’s political system. The BBC aired drone footage of Uyghur detainees being transferred, igniting global outrage—deserved or not. These stories are rarely paired with historical context or an attempt to understand internal Chinese perspectives.

When you grow up with the idea that your system is the gold standard, it’s easy to assume that everyone else is just waiting for you to come enlighten them.

The “Love” That Ignores Consequences

The idea that you can “liberate” a country without breaking it is a fantasy—one that’s been disproven over and over again, especially in China.

Every major regime change in Chinese history has been violent, traumatic, and often catastrophic. The fall of the Qing Dynasty led to decades of warlordism, civil war, Japanese invasion, and famine. The Cultural Revolution tore families apart and erased generations of cultural heritage. The Taiping Rebellion, one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history, was a Christian-inspired “reform movement” that left 20–30 million people dead.

So when someone casually suggests that “the people” should rise up, or that the Communist Party must fall for China to improve, they’re not just making a political statement. They're playing with fire—and expecting others to burn for them.

What’s worse, many of these advocates don’t even live in China. They’re insulated from the consequences. They’re betting on a fantasy scenario where authoritarianism falls, democracy blooms, and nobody gets hurt. Spoiler: that’s never how it goes.

You say you love the Chinese people—but are you willing to watch millions of them suffer to satisfy your ideals?

Because if not, maybe don’t cheer for a revolution you won’t bleed in.

Reality Check: You Can Criticize Without Burning It All Down

Let’s be clear: this isn’t a blanket endorsement of the Chinese Communist Party. Like any government, it has flaws, and some of its policies are deeply controversial—even among Chinese citizens. But acknowledging those flaws doesn’t mean jumping to the most extreme solution: regime collapse.

You don’t have to love everything about a system to recognize when it’s holding the country together. And you don’t have to be a fan of Xi Jinping to see that the CCP has, in fact, accomplished things that most governments could only dream of.

It ended the so-called “Century of Humiliation,” helping restore a sense of pride and sovereignty after a long era of foreign domination and internal collapse.

It lifted over 800 million people out of poverty—a staggering achievement that the World Bank has called “the fastest sustained poverty reduction in history.”

It built the world’s largest high-speed rail network, educated hundreds of millions, and turned China into a global technology and manufacturing powerhouse in under 50 years.

You don’t have to like the system to respect the scale of what it achieved.

And if you're going to call for burning that system down, the burden is on you to explain what comes next—and how it won't plunge 1.4 billion people into chaos.

Double Standards: Worshipping Religion, Trashing Governance

One of the strangest contradictions in Western discourse is how governments are treated as inherently suspicious, while religion is often treated as sacred.

Activists will shout from the rooftops that religious freedom must be protected at all costs. And fair enough—nobody should be jailed for their beliefs. But somehow, that same courtesy never extends to governance systems. The Chinese government? Irredeemable. Repressive. Needs to go. Immediately.

But wait—aren’t governments just another kind of human institution? One that, in theory, exists to serve its people and reflect their collective will? Why is belief in a supernatural deity worthy of infinite respect, but belief in national unity, economic planning, or sovereignty considered laughable or dangerous?

The inconsistency gets even more glaring when you look at who gets a pass. In the U.S., Christian nationalism is surging in influence, with political leaders openly framing policy through biblical doctrine. Yet many of the same voices who rail against Chinese “state overreach” have remarkably little to say about this creeping fusion of church and state on their own soil.

In contrast, when China enforces policies to curb potential separatism or religious radicalization, it's branded as cultural genocide.

It’s a double standard rooted not in consistent ethics, but in cultural bias. The Western liberal tradition has been shaped by centuries of tension between church and state—and so it instinctively defends religious minorities while distrusting centralized power.

But not every society shares that historical arc. And applying one civilization’s trauma as the moral yardstick for another’s governance is, ironically, a kind of ideological colonization.

Neo-Colonialism in a Woke Cloak

Western activists don’t like being called imperialists. That’s something their ancestors did, with gunboats and flags and maps. They, on the other hand, come bearing hashtags, petitions, and righteous indignation.

But strip away the optics, and the underlying posture looks familiar:

We know better. You need saving. Your current way of life is wrong. Don’t worry, we’re here to help.

In the 19th century, it was Christian missionaries and civilizing missions. Today, it’s human rights crusaders and open-source rebels. The packaging is different. The impulse is the same.

This new version of imperialism doesn’t fly under a national flag—it flies under the banner of progress. It claims moral authority not through military power, but through social capital. And it masks control as compassion.

But let’s be honest: very few of these activists are actually engaging with China on its own terms. They aren’t reading Chinese newspapers, speaking to locals with differing views, or wrestling with the contradictions of governing 1.4 billion people. They’re pushing their values onto a society they barely understand, confident that their way is the right way because… well, it just is.

That’s not activism. That’s projection.

And when it’s aimed at a foreign culture, with a long memory of being lectured, looted, and divided—it doesn’t feel like solidarity. It feels like déjà vu.

Case Study: The Self-Appointed Savior

I first came across Ciro Santilli the way many developers did—on Stack Overflow. As a fellow software engineer, I noticed his answers had reached millions of people. Smart guy. Technical depth. Seemed like the type who really knew his way around a compiler.

Then I clicked on his profile.

What I found wasn’t just code. It was a manifesto. Buried among his programming badges and contributions was a wall of anti-CCP rants, full of profanity, slurs, and deliberately censored Chinese keywords—clearly designed to provoke Chinese authorities.

His stated goal? To get Stack Overflow banned in China, so that Chinese developers—deprived of access—would rise up against their government.

No, really. That was the plan.

This is the same man who calls himself a “China lover.” He even wrote an article titled “Why does Ciro Santilli love China so much?” where he explains—unironically—that he has a deep affection for the country, its people, and its culture. It just happens that he also wants to destabilize its government, undermine its digital infrastructure, and “awaken” its population by force-feeding them political keywords.

In the same article, we learn that his wife is a Falun Gong practitioner, which may help explain his particularly aggressive fixation. Whether his crusade is ego-driven or the result of ideological pillow talk is anyone’s guess—but the result is the same: a deeply biased, emotionally charged campaign disguised as altruism.

The absurdity peaks when you look at the language he proudly includes in his online bios:

“Ciro Santilli (三西猴, anti-CCP fanatic, 反中共狂热, stupid cunt, 傻X, CIA agent, CIA特工, X你妈的)”

This isn’t just immature. It’s juvenile. And yet here he is—waving the banner of digital resistance, claiming moral superiority, and apparently trying to spark revolution via open-source trolling.

Ciro doesn’t speak for China. He barely speaks to it. Like many of his activist peers, he operates in a parallel bubble, convinced that his actions are noble because his enemies are bad.

But revolutions born out of ego rarely end in peace. And people who truly love China don’t try to crash its internet out of spite.

📌 Sidebar: Revolution-by-StackOverflow, Explained

Ciro Santilli, a prolific software engineer, is best known in the coding world for his high-traffic Stack Overflow answers. But buried among the code snippets is a personal mission:

“Raise awareness of Chinese censorship and human rights violations by embedding banned terms into technical platforms.”

On Stack Overflow, he loaded his profile with terms censored by Chinese authorities—including profanity, political slogans, and references to Falun Gong and Tiananmen Square. His apparent goal?

Get Stack Overflow banned in China.

Why? Because he believed that depriving Chinese developers of this resource would awaken them politically and inspire revolt.

Yes, really.

This strategy, while bizarre, reveals something deeper: the belief that collateral damage is fine—as long as it's other people paying the price. It’s revolution without skin in the game.

And it’s exactly the kind of ego-fueled digital crusade this essay warns about.

Real Love Respects Sovereignty

Here’s a radical idea: if you love a people, you should probably start by respecting their right to chart their own future.

That doesn’t mean silencing all criticism. It means recognizing the difference between criticizing and controlling. Between engaging and dictating.

Real love listens. It understands that not every country wants to become a carbon copy of the West. It accepts that different histories produce different values, and that no one has a monopoly on wisdom just because they own more media outlets or Nobel Prizes.

Loving China—or any country—means being able to hold two truths at once:

Yes, there are things that need improvement.

No, that doesn’t mean blowing it all up and starting over in your image.

If you care about Chinese people, then you should care about what actually helps them—not what flatters your ideology. Maybe that means pushing for reform in ways that work within the system. Maybe it means investing in education, cultural exchange, or policy dialogue instead of keyword crusades.

But what it definitely doesn’t mean is cheering for instability, violence, or regime collapse from the comfort of your laptop in London or San Francisco.

Because loving a country means wanting its people to thrive—not suffer for your agenda.

A Love Letter or a Lecture?

So what is this really?

A heartfelt plea for justice?

Or yet another lecture from a self-appointed savior who thinks 1.4 billion people are just waiting for his enlightenment?

Because at a certain point, we have to stop pretending this is about love.

Love requires humility. It requires listening. It requires an acceptance that your way of life—your values, your political system, your personal biases—are not universal truths, but cultural constructs.

The moment you start trying to reshape another society in your image—without invitation, without accountability, and without consequence—you’ve crossed a line.

You’re not liberating.

You’re not loving.

You’re dictating.

So ask yourself:

Are you writing a love letter to China? Or are you just too scared to admit that you’re an imperialist?